To answer some questions posed by a participant of the seminar of Tokyo Lacanian School

I will answer here those questions posed by a participant of my seminar:

1. What is the Es in Freud’s second topic?

2. What is sublimation in Lacan’s teaching?

3. What is the difference and/or the relation between those three terms: das Ding, la Chose and object a?

1. Answer to the first question: What is the Es in Freud’s second topic?

The English translation of the three instances composing Freud’s second topic – das Ich, das Über-Ich and das Es – is, as you know, the ego, the super-ego and the id, and the current Japanese translation is 自我,超自我 and エス.

You see that while Freud uses his own language, that is, German, in English they don’t use English words but Latin ones, and in Japanese they use Chinese words for das Ich and das Über-Ich, and for das Es they gave up translating and contented themselves with writing approximately the German pronunciation of the word Es with Katakana. In French they say le moi, le surmoi and le ça.

The word Es in German is the singular neuter third person pronoun, and like the word it in English, it is also used with impersonal verbs such as regnen (rain): es regnet (it rains).

Freud borrowed the expression das Es from Georg Groddeck (1866-1934) who says in his Buch vom Es (Book of the Es):

Ich bin der Ansicht, daß der Mensch vom Unbekannten belebt wird. In ihm ist ein Es, irgendein Wunderbares, das alles, was er tut und was mit ihm geschieht, regelt. Der Satz: »Ich lebe« ist nur bedingt richtig, er drückt ein kleines Teilphänomen von der Grundwahrheit aus: »Der Mensch wird vom Es gelebt«. Mit diesem Es werden sich meine Briefe beschäftigen. Sind Sie damit einverstanden?

Und nun noch eins. Wir kennen von diesem Es nur das, was innerhalb unseres Bewußtseins liegt. Weitaus das meiste ist unbetretbares Gebiet. Aber wir können die Grenzen unseres Bewußtseins durch Forschung und Arbeit erweitern und wir können tief in das Unbewußte eindringen, wenn wir uns entschließen, nicht mehr wissen zu wollen, sondern zu phantasieren. Wohlan, mein schöner Doktor Faust, der Mantel ist zum Flug bereit. Ins Unbewußte…

I hold the view that man is animated by the Unknown. There is within him an Es, something wondrous that directs what he himself does and what happens to him. The proposition “I live” is only conditionally correct, it expresses only a small and superficial part of the fundamental truth: “Man is lived by the Es”. With this Es, my letters will be concerned. Are you agreed?

Yet one thing more. Of the Es, we know only so much as lies within our consciousness. Beyond that, the greater part of its territory is untrod. But by search and effort we can extend the limits of our consciousness, and press far into the realm of the unconscious, if we can bring ourselves no more to desire knowledge, but only to fantasy. Come then, my pretty Dr. Faust, the mantle is spread for the flight. Forth into the unconscious…

Thus, the word Es means basically something in human being that is unknown and indefinable for us and that is nevertheless more fundamental, truer and realer than our self-awareness.

You could rightly substitute “something” (etwas) for “Es”. And because the Japanese language doesn’t have pronouns such as Indo-European languages have,「何か」(something) would be an appropriate Japanese translation of Es.

For example, Lacan says: « dans l’inconscient, ça parle » (Écrits, p.437). In Bruce Fink’s translation, “in the unconscious, it speaks”. In German we could say: „im Unbewussten spricht Es“. And in Japanese:「無意識において,何かが語る」.

We can situate the structure of Freud’s second topic in the structure of alienation and in that of the discourse of university as shown in the following schemas:

Le discours de l'université

That is, the Es is the subject $ in the locality of what doesn’t cease not to be written (the locality of the impossible or of the ex-sistence: the place of production); the Über-Ich in the place of what obturates the apophatico-ontological hole (the place of truth) ; the Ich in the place of consistency (the place of agent).

In function of the Es that speaks in the unconscious, the object a on the edge of the apophatico-ontological hole (the place of other) is the voice.

As regards the relations between the three instances of the second topic, Freud says in Das Ich und das Es that the Über-Ich is „Vertreter des Es“ (representative of the Es) against the Ich. This structure is formalisable in Lacan’s mathematico-topological schema of alienation (the discourse of university) as follows:

The Über-Ich S1 represents the Es $ against the Ich S2.

This structure of representation is more evident in the following schematisation of Urverdrängung of the subject $ (Es) by the master-signifier S1 (Über-Ich).

This process of Urverdrängung corresponds to the structural transformation from the discourse of master to the discourse of university.

Thus, we can see that Lacan’s formula « un signifiant S1 représente le sujet $ pour un autre signifiant S2 » (a signifier represents the subject for another signifier) formalises exactly Freud’s statement concerning the relation of Ich, Über-Ich and Es.

2. Answer to the second question: What is sublimation in Lacan’s teaching?

Sublimation of desire is one of central themes in Lacan’s teaching concerning the end of analysis. This fact is evident especially in his Seminar VII Ethics of Psychoanalysis, but not so after his Seminar XVII. Nevertheless, we can see also there Lacan think of sublimation in hidden ways, for example when he talks of feminine jouissance and mystic jouissance in his Seminar XX Encore or of saints in Television, that is, those forms of jouissance which are not phallic (jouissance phallique) nor pregenital (plus-de-jouir), and also when he talks of love as is defined in this way: “love is sublimation of desire” (cf. Seminar X Angst).

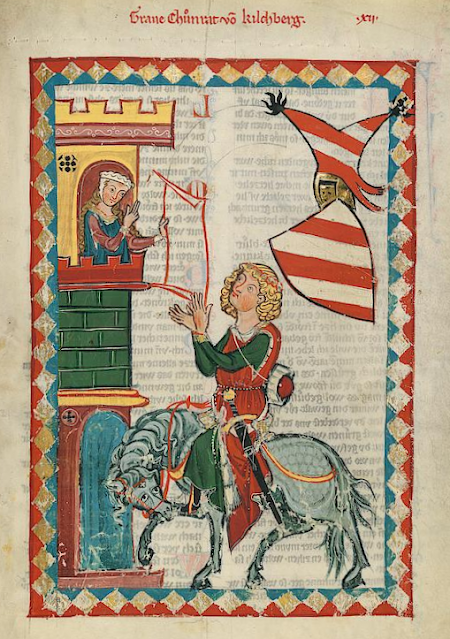

In that context, he always sees the model of love as sublimation of desire in amour courtois, that form of love where the satisfaction of sexual desire in carnal relationships is absolutely forbidden so that the man who loves a Lady can do nothing but think and sing of her in his poetic creations, that is, in sublimational ways. And in this form of sublimation, that is, in artistic creation, there is a certain kind of jouissance which we can call sublimational jouissance.

Lacan talks of amour courtois not only in his Seminar VII but also in his Seminar XX Encore. And you can find the word amour in the enigmatic title of his Seminar XXIV L’insu que sait de l’une-bévue s’aile à mourre. Those fragments of lalangue say “l’insuccès de l’Unbewusst, c’est l’amour”, that is, “unsuccess of the unconscious is love”. By the way, Seminar XXIV is the only one among all Seminars of Lacan that contains the word amour in its title, even if in a cryptic way.

Why must there be sublimational jouissance at the end of analysis? Because as far as desire continues slipping unsatisfied in metonymic way, analysis cannot arrive at its end. But the satisfaction of desire (that is, jouissance) cannot be pregenital jouissance (what Lacan calls plus-de-jouir) because that form of jouissance is nothing but neurotic fixation on pregenital objects, nor be phallic jouissance because there is no sexual relationship.

Lacan’s proposition “there is no sexual relationship” means this: there is no phallus such as supposed by Freud when he formulates that development of sexual drive must arrive at the mature stage called genital organization where pregenital drives (partial drives) are integrated into the genital drive under the primacy of phallus so that the sexual drives can serve for reproduction.

You might think that it would be self-evident to suppose that sexual drives mature to be able to serve for reproduction. But no, that is a teleological (metaphysical) supposition susceptible to critique.

In fact, Lacan formulates already in his Rapport de Rome (Écrits, p.263) a critique against Freud’s teleology in this expression: “mythology of maturation of drives”. That is to say: the phallus under primacy of which the development of sexual drives must attain maturity is mythological. And what real does this mythological phallus hide? The real that there is no sexual relationship, that is, the said phallus is impossible (doesn’t cease not to be written).

Thus, the third form of jouissance which is not phallic nor pregenital is necessary if analytic process can attain its end. And this end consists in sublimational jouissance, that is, love as sublimation of desire.

In his Seminar XX Encore, Lacan presents feminine jouissance as a jouissance beyond phallic jouissance (and, of course, beyond pregenital plus-de-jouir), but we must insert there a footnote: feminine jouissance per se is not the sublimational jouissance required for the end of analysis, but is a somatisational form of non-phallic and non-pregenital jouissance.

On the contrary the sublimational jouissance is not somatisational but existential.

If Lacan talks of feminine jouissance, it is for the purpose of considering what might be the sublimational jouissance on the basis of feminine jouissance which Lacan makes use of as a concrete model of the unknown jouissance of sublimation.

Now I would say that the sublimational jouissance consists in the emergence of the open hole of the subject $ in the structure of the discourse of analyst. And this emergence occurs in the process of structural transformation from the discourse of university (structure of alienation) to the discourse of analyst (structure of separation), where the subject $, hidden in the place of what doesn't cease not to be written in the discourse of university, emerges now in the form of the edge of the apophatico-ontological hole in the discourse of analyst.

In the discours of analyste, the subject $ which forms the edge of the apophatico-ontological hole, is imaginary in the sense that it has now its own consistency as the edge, is real in the sense that now it doesn't cease to be written, and is symbolic in the sense that it forms now a hole. The sublimational jouissance consists in this realisation of the subject $ as consistent and real hole.

And now the subject $, separated from the object a and the knowledge S2, represents the Name of God S1 which is foreclosed in the place of what doesn't cease not to be written. This structure $/S1 is the structure of being saint.

3. Answer to the third question: What is the difference and/or the relation between those three terms: das Ding, la Chose and object a?

When Lacan talks of das Ding in his Seminar VII, he does so as if only in reference to Freud’s text Entwurf einer Psychologie (Project of a Psychology), but I think it is very certain that he also thinks of Kant’s Ding an sich and of Heidegger’s text Das Ding.

Anyway, in his Entwurf Freud considers Ding evidently in Kantian way because he says for example that “the perceptual complexes [ Wahrnehmungskomplexe ] are dissected into an unassimilable component (das Ding) and one known to the ego from its own experience (attribute, activity)”.

Heidegger’s conference Das Ding is collected with Logos and some other texts in his book Vorträge und Aufsätze (1954). Because Lacan himself translated Logos in French in 1955, it is very certain that he read Das Ding too immediately after the publication of the book.

What Heidegger calls there Ding is the same thing as Heraclitus’ Logos, that is, the locality of Ἀ-Λήθεια (I will here explain no more because that would be too long).

Anyway, what is concerned in the third question is this proposition Lacan presents in the session of the 20th January 1960 in his Seminar Ethics of Psychoanalysis:

La sublimation élève un objet à la dignité de la Chose.

Sublimation elevates an object to the dignity of Thing.

There Lacan says Chose for translation of Ding.

Now, what does this proposition mean?

It means, I think, the structural transformation from the discourse of university to the discourse of analyst, where the subject $, emerging from the place of what doesn't cease not to be written (the right lower place, the place of production) to the place of what doesn't cease to be written (the right upper place, the place of other), replaces the object a which is now separated from the subject $ and displaced to the left upper place (the place of agent).

What Lacan calls in that proposition Chose (Ding) is the subject $.

In the structure of the discourse of university, the subject $ is hidden in the place of what doesn't cease not to be written (the impossible) just as the Ding an sich is hidden as something impossible to perceive or cognize (because, according to Kant, what we can perceive or cognize is only phenomenon or representation of Ding, not Ding an sich selbst).

And in the structural transformation from the discourse of university to the discourse of analyst the subject $ emerges from hiddenness (Verborgenheit: λήθη) to unhiddenness (Unverborgenheit: ἀλήθεια) just as Heidegger's Ding is the locality of Ἀ-Λήθεια.

The difficulty you meet when you read Lacan is mostly attributable to this: what matters in Lacan's teaching is not a static structure but a structural transformation which allows the emergence of the hole of the subject $ from the place of what doesn't cease not to be written (the impossible) to the place of what doesn't cease to be written (the necessary).

Heidegger thinks of this apophatico-ontological emergence when he says phenomenology. And that is the meaning of his proposition: "Ontology is possible only as phenomenology". N.B.: the "ontology" which matters in Heidegger's thinking is always "apophatic ontology", not the traditional (that is, metaphysical) ontology, because he always focuses his question on Seyn (Being), not on the metaphysical (substantial) Being.

And this phenomenology is necessarily dialectical because what comes into question is the process of desalienation (liberation from alienation). The subject $ is alienated in the structure of the discourse of university in the sense that it is subjected and represented at the same time by the master signifier S1 and the object a. And it emerges desalienated in the structure of the discourse of analyst, where the term "desalienated" means this: the subject $ discards the object a and it is now the subject $ that represents the impossible name of God S1.

.jpg)

.jpg)